page 2 • Pop-Mekhanika – a National Bolshevik Party band?

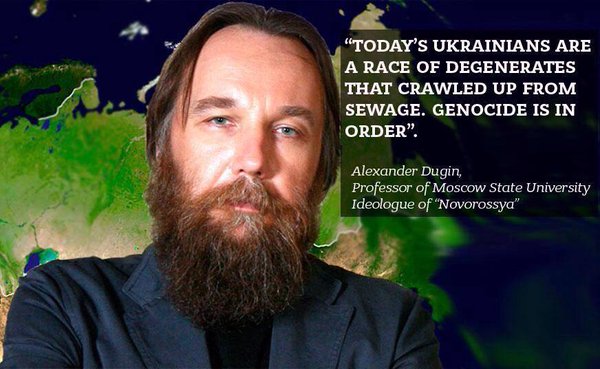

The year 1995 saw a significant change in Sergey Kuryokhin’s activities: having met Eduard Limonov and Alexander Dugin, the founders of the National Bolshevik Party (NBP, 1993), he turned to politics and adopted a totalitarian, anti-Western position.

The NBP operated from 1993 to 2007 in the form of аn “inter-regional public organisation” (mezhregional’naia obshchestvennaia organizatsiia / межрегиональная общественная организация); in 2007, however, it was accused of extremism and banned by Moscow City Court.[1] The NBP started as a sort of eclectic totalitarian movement, adhering to the ideas of Italian fascism while also absorbing Crowleyan positions and assembling both ultra-right and ultra-left ideologies. Since the movement had not been granted the status of a party, Dugin participated in the Duma elections on 17 December 1995 as an independent candidate. He ran as a candidate for Saint Petersburg constituency no. 210 under the slogan: “The secret will be revealed”.[2]

In the first of its twenty-six points, the party programme from 1994 stipulated:

The essence of National Bolshevism is ravaging hatred towards the ANTIHUMAN trinitary system of liberalism / democracy / capitalism. The National Bolshevik is an insurgent with a mission to raze the SYSTEMS to the ground. A traditionalist, hierarchical society will be built on the basis of the ideals of spiritual masculinity and social and national justice.[3]

The main goal was stated in point no. 3. It also formed the basis of the “Eurasian Movement” Dugin founded after leaving the party in 1998:

The global goal of National Bolshevism is the creation of an Empire stretching from Vladivostok to Gibraltar, based on Russian civilization. This goal will be achieved in four stages: a) the transformation of the Russian Federation into a national state of Russia by means of a Russian Revolution, b) the accession of the territories of the former Soviet republics that are inhabited by Russians, c) the Eurasian peoples of the former USSR uniting around the Russians, and d) the creation of a gigantic continental Empire.[4] [5]

Point 7 is more specific about how this goal is to be achieved:

We denounce the Belavezha Accords and its consequences; the borders of Russia will be revised. We will unite all Russians within a single state. Wherever Russians exceed 50% of the population in territories of secessionist “republics”, these territories will be united with Russia via local referenda supported by Russia (Crimea, Northern Caucasus, Narvsky district etc.). Separatism of national minorities will be suppressed relentlessly.[6]

The party programme committed itself to reconquering Russia, stating “Russia will belong to us”, and promised the socially deprived youth they would become like “Dzerzhinsky, Goebbels, Molotov, Voroshilov, Ciano, Göring, and Zhukov” (point 24). The party’s motto was “Russia is everything, the rest is nothing” (point 26, "Россия – все, остальное ничто!").

The party’s aspiration to dominate an empire incorporating satellite states from Vladivostok to Gibraltar – an aspiration which was notably both imperialistic and totalitarian in nature – extended far beyond what had once “belonged” to the Soviet Union. But there was one point in this programme that was not totalitarian in spirit, namely point no. 15, pertaining to culture, and this particular point contradicted all the other points of the programme:

The NBP is strongly convinced that culture should grow like a wild tree. We are not planning to cut it back. There shall be complete freedom. “Do what you want” will be the only law you have.[7]

This point demonstrates Dugin’s assimilation of Crowley’s main dogma from the Book of Law – The Law of Thelema: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.”[8]

I would, however, deem it Dugin's postmodern, “anything goes” interpretation of Crowley, in whose understanding one’s true will can only be searched out and achieved through a complicated process predicated on magic. This diluted version of Crowley may have represented a concession on the part of Dugin towards his target group or towards the co-founder of the NBP, Eduard Limonov. Limonov, a well-known and highly controversial Russian writer, spent many years in in exile before returning to Russia in 1991, at which point he became a political activist. In his “The Book of the Dead” from 2013, he mocked Dugin’s esoteric approach as that of a “skilful fairy-teller, a conjurer who hypnotised young people with enticing myths”,[9] while nevertheless still acknowledging the fact that it had helped the party to consolidate.

In contrast to Limonov, Kuryokhin was greatly interested in Dugin’s knowledge of philosophical and esoteric literature, especially with regard to Aleister Crowley. The Englishman Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), a person of extraordinary occult knowledge and a remarkably prolific writer, had been the leader of the British Branch of the Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO)[10] and a medium to a spirit by the name of Aiwaz or Aiwass. According to Nevill Drury, “Crowley believed that Aiwass was a messenger from the Egyptian deity Horus, the flacon-headed god that had the sun and the moon for his eyes. Crowley came to believe that he was Lord of the Aeon of Horus, which began in 1904, replacing Christianity and the other major religious traditions of both West and East.”[11]

Whether Kuryokhin met Limonov before meeting Dugin[12] or after meeting Dugin[13], there can be no doubt that Dugin’s influence on Kuryokhin was more important than Limonov’s.[14] Kuryokhin appreciated Dugin not only as a political companion, but also as a spiritual partner. Dugin, on the other hand, saw in Kuroykhin a personality capable of recreating “pre-cultural” forms of priesthood via the medium of Pop-Mekhanika performances. To Dugin, this was of great significance. The following quotation is from his essay The Entity’s 418 Masks, dedicated to Sergey Kuryokhin and Pop-Mekhanika No. 418.

Sergey Kuryokhin has always not just pursued his creative quest, but persistently and consistently recreated the organic unity which came before the classical, modern and hyper-modern (rock music, avant-gardism) periods. His perseverance in re-establishing the main characteristics of the traditional, “pre-cultural” and archaic priesthood is striking.[15]

But did Dugin’s influence mean “Pop-Mekhanika” was an NBP band? This is what Andrei Rogatchevski and Yngvar B. Steinholt argue in their 2015 article, “Pussy Riot’s Musical Precursors? The National Bolshevik Party Bands, 1994-2007”, which counted Pop-Mekhanika among the (mostly punk and metal) bands “orbiting the NBP”.[16]

Yet Pop-Mekhanika had a ten-year history behind it before Kuryokhin ever set out to give it a new mission. The main period of the band's activity had ended in 1991, long before Kuryokhin became interested in Dugin, and between 1992 and 1995, PM performances took place only sporadically. Pop-Mekhanika No. 418 was the only performance directly connected to the National Bolshevik Party – as part of Dugin’s election campaign and indeed accompanied by distribution of the party’s newspaper “Limonka” and other “red trash”[17] in the foyer of the Lensoviet Palace of Culture, where the concert took place. It isn’t clear whether Limonov or Dugin came out with any party slogans during the performance, as (incomplete) video documentation only shows their esoteric speeches.

The concert itself was essentially a reproduction of the Helsinki performance staged three weeks earlier, containing the same “Crowleyan” elements, plus readings from Dugin and Limonov. Dugin stated that it was “actually a Crowleyan performance, illustrating the end of the aeon of Osiris”.[18] In a press conference given prior to PM No. 418, Sergey Kuryokhin declared, “This concert starts a new line in both Pop-Mekhanika's and my own creative work… Roughly speaking, this thread has to do with religious propaganda. I understand 'religious propaganda' as meaning the propagation of Religion with a capital R.”[19] The irony is that the NBP abstained from religious positions as such.

Pop-Mekhanika No. 418 was to become Kuryokhin’s very last PM performance; in the spring of 1996, he fell ill and died shortly afterwards. It thus remains a matter of conjecture whether – or in what way – PM's participants would have continued their collaboration with Kuryokhin following the scandal created by this concert. Alexander Kushnir, who starts his biography of Sergey Kuryokhin with a – highly embellished – description of the Helsinki performance (omitting any mention of Crowley – possibly deliberately), quotes the negative reactions of two of the musicians: Vladimir Volkov (“I was experiencing qualms of conscience on account of the fire, the crosses, and all that scary stuff”) and Alexander Kurashov (“It was so creepy”).[20] Bearing in mind how they reacted to the performance in Helsinki, it is possible to imagine how they may have reacted to the performance in Saint Petersburg. While it is conceivable that the other participants may have responded to the performance in a less critical way, it must still be borne in mind that the musicians, performers, and artists were all members of their own separate bands and groups, and they had joined Kuryokhin for the purpose of pleasure, not so as to gain a dubious reputation.

Taking all these things together, we can establish that PM No. 418 was the first of its kind, namely: National Bolshevik on the outside, but Crowleyan on the inside. Kuryokhin’s announcement notwithstanding, the question of whether he would have perpetuated his new concept remains in doubt to this day. Bearing in mind that what had taken place was a one-off, calling Pop-Mekhanika a National Bolshevik Party band would seem to be going too far.